I have recently received a question from one of our newsletter subscribers. They write:

“Firstly, I want to say, I really enjoy reading your articles and enjoy building the knowledge that those articles bring.

My role has transitioned from maintenance supervisor to maintenance planner. In my new role, I have the responsibility of reducing the outstanding work orders in our CMMS whilst prioritising the new work orders being generated.

What are some guidelines I can use for prioritizing work orders to be able to do the correct work now? The old system relied on personnel entering their work orders into the system and prioritizing the WOs as they see fit. This is not realistic as everyone sees their WOs as [highest] priority.”

This is a great question, and one that this article will attempt to answer.

What is a Work Order Priority?

The first issue to be addressed in determining how to establish the priority for each Maintenance Work Order is to establish what, exactly, a Work Order Priority is. Almost every Computerised Maintenance Management System (CMMS) contains a field where you can set the work order priority, but few define exactly how it is to be used (which in turn determines what it should be).

While there are a number of different interpretations of Work Order Priority that are possible, our view is that the Work Order Priority should represent an indication of the level of business risk that relates to the fault or failure that the work order is intended to address. The higher the overall risk associated with the fault or failure, then the higher the priority.

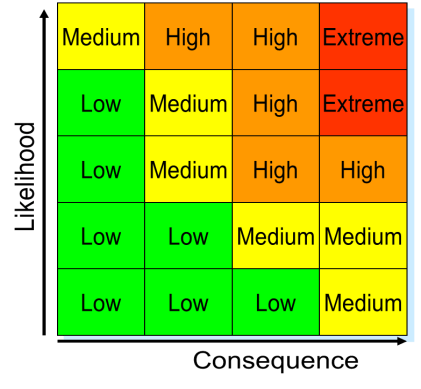

As risk is generally represented as the combination of consequences and likelihood, when assessing the priority of a work order, the following questions should be asked:

- If we do not perform this work, and the equipment suffers a functional failure, in what way would this impact on the achievement of the organisation’s objectives, and how large would that impact be?

- If we do not perform this work, how likely would the equipment be to suffer that functional failure within the next (predetermined) time period?

The first of these questions assesses the potential consequences of not performing the work, and the second questions assesses the likelihood of those consequences eventuating. These can then be combined in a risk matrix similar to the one shown in Figure 1 below to give an overall Work Order Priority.

Applying Work Order Priorities in practice

So far it seems pretty simple, but let’s now explore some of the intricacies of applying this in practice.

Assessing consequences

The phrase “functional failure” in the context above means exactly what it means in Reliability Centered Maintenance. What this means is that we first need to understand which function(s) are likely to be impacted by the fault or defect. RCM tells us that equipment can have many functions in addition to its primary function. For example, a conveyor, in addition to its primary function of being able to transport material from one location to another at a specified minimum rate, may have secondary functions that relate to Safety, Protection, Control, Containment etc. Further, RCM tells us that equipment can suffer a functional failure, in some cases, not just by failing to operate at all, but by failing in such a way that, although still operating, it fails to meet one or more specified minimum performance standards. So careful thought is required when assessing each work order to understand which functions and associated functional failures may be impacted by the fault.

Second, in order to ensure consistency in prioritisation amongst different equipment items, we need to understand the impact of the possible functional failure on overall business objectives. Bear in mind here that by “objective” I am using the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) definition of an objective as being a “result to be achieved”. Those objectives could relate to the achievement of target performance levels in the areas of production throughput (failure to meet production targets), costs (failure to meet cost targets), or risk (failure to meet safety, environmental or social responsibility targets).

So, when assessing consequences, it is important to be thorough, and it is also important to take a “big picture” view of the nature of these consequences on the overall business.

Assessing likelihood

Assessing the likelihood of failure requires you to determine, in advance and in a consistent manner, the time period over which the likelihood of failure is to be assessed. For example, are we assessing the likelihood that the equipment will fail within the next week, within the next month, the next year, or some other time period? The correct answer will depend on your situation, but I suggest that the time period should be consistent with your work order scheduling horizon. If, for example, you issue a work schedule for the maintenance execution team to complete once per week, then the timeframe for assessment of likelihood should also be weekly. Bear in mind that if the nature of the fault is such that the equipment will continue to degrade, then the likelihood of failure will increase as time passes, and so the work order priority should be reassessed periodically to take account of this. Too many organisations, in my experience, determine the work order priority when the work order is first raised, and then never reassess that priority (at least until, unfortunately, the equipment fails “unexpectedly”).

Who should set Work Order Priorities?

As you can see from the above, setting the priority for a work order requires knowledge of:

- The current condition of the asset for which the work order has been raised

- The likelihood speed of progression from current condition to a functionally failed state

- The potential impact of this failed state on operational and organisational objectives, given the current situation regarding overall plant status, production plans, stockpile levels, potential workarounds etc.

It is unlikely that any one person will have sufficient knowledge of all of these items to make a fully informed decision regarding work order priority. For this reason, I highly recommend that work order priorities be established jointly by maintenance and production/operations personnel, each of whom will bring different knowledge and skills to the decision-making process. Most likely, the production and maintenance representatives will be front-line supervisors, as they have the most intimate knowledge of the plant, but higher-level management supervision and/or involvement is likely also to be of value, in order to ensure that decisions align with overall management priorities.

Work Order Priorities and scheduling work orders

The next question to ask is what we use Work Order Priorities for. Can we, or should we, always schedule the highest priority work orders for completion first? Unfortunately, the answer is “no”.

We should, however, as a general rule, start work on the highest priority work orders first, but when the work is actually completed will depend on a number of other factors. For example, if the work order requires spare parts that are not in stock, then there is little point in scheduling the work for completion until such time as the parts are actually available. For long lead-time items, this may be several weeks in the future. High work order priority may, however, indicate that acquisition of these spare parts is expedited with some urgency. Similarly, if, to perform the work, we need to shut down the equipment, then the work will need to be scheduled for a time that has minimum overall impact on plant objectives, and performance of this work may be completed at the same time as a number of other work orders that require equipment to be shut down.

Sometimes we may also schedule work for completion that is assessed as “lower” priority using the risk matrix approach. For example, from time to time Work Orders can be raised for Maintenance personnel to execute that are not directly related to impending equipment failures. These are often proactive tasks that relate either to equipment preservation or improvement activities which are intended to improve overall equipment reliability. For example, painting handrails is generally not done to prevent impending failure, and if assessed using a risk matrix would almost always be rated as low priority – at least until the handrails were in danger of failing – but if we ever get to that stage, then painting them is going to have very little effect!

These types of work orders do have a positive impact on achievement of organisational objectives, but the likelihood of failure for these work orders is low. If subjected to the risk matrix approach, these will typically always be assessed as having low priority, and therefore will never be scheduled for execution, unless we make a proactive decision to get these done. It is always worthwhile scheduling some of this work for completion each week. This work often can also be conveniently deferred if more urgent work arises in the meantime (such as breakdowns).

Conclusion

I hope that this article has helped to provide some insights in this area. How do you currently set Maintenance Work Order Priorities within your organisation?

If you have other questions you would like to have answered, please feel free to contact me, and I will attempt to answer these in future articles.