Foster motivated attitudes towards change

Any form of change initiative must successfully address the question of “what’s in it for me” for those being asked to change. In other words, there must be some form of greater reward for individuals and groups if they adopt the new, desired behaviours, than if they continue to behave in the old, undesirable way. These rewards can be both financial and non-financial, but the most successful change initiatives incorporate a blend of the two.

It is also important to assess the existing financial and non-financial reward systems, and identify any elements of the existing reward systems which are incompatible with the desired behaviours.

This is the third in a series of 6 articles on moving from a repair-focused to a reliability-focused culture.

Articles in this series

Consider personal rewards when creating order from chaos

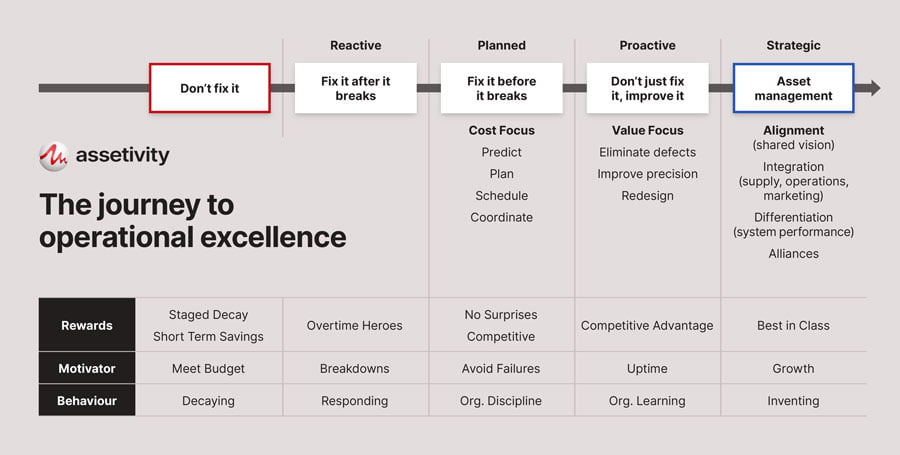

Another way of viewing the journey from repair-focused to reliability-focused culture is that outlined by Ledet, as illustrated in Figure 2. There are several things to point out in this model, in terms of incentives and rewards. First, put yourself in the position of being a tradesperson in a reactive maintenance environment. There are a number of personal rewards associated with working in this type of environment, such as:

- The challenge and variety associated with never knowing what you will be working on next

- The financial rewards associated with overtime and callouts

- The personal rewards associated with being the “hero” that can fix breakdowns as quickly as possible, and get the plant back on-line

- The satisfaction of being able to, at short notice, respond to the demands of production personnel – some would call this having a “customer focus”

If you then move into the Planned maintenance phase, with its focus on systems, rules, procedures and discipline, then all of these rewards disappear. In its place, from a tradesperson’s view, is routine, inspections, and minimal challenge. As one tradesperson once said to me – “It’s like Groundhog Day”. While there may be some people who relish the certainty that goes with this routine and discipline, it is unlikely to be the same type of person that thrives in the semi-chaos of a reactive maintenance environment – so there is a need to provide tradespeople with different rewards to replace those which they are now missing out on.

Money talks

A clear candidate, in order to align rewards with desired behaviour, is to remove the payment of overtime for callouts and for performing unplanned work. The best maintenance organisations in Australia now pay tradespeople a fixed salary, rather than hourly rates, thereby removing the financial reward associated with breakdowns and after-hours rework. At another organisation, moving tradespeople from hourly rates to fixed salaries had an immediate effect on shopfloor attitudes to callouts – where previously, tradespeople would, without question, attend to a callout, on the change, tradespeople would question the need for a callout, and take a proactive role in minimising the number of callouts required.

Other rewards that could be provided include the payment of bonuses for the achievement of target levels of planned work, reliability targets or other measures of desired performance – or providing awards or celebrations for these achievements, in the same way as many organisations already do for the achievement of safety targets.

Managing upskilling as a reward

Once the organisation moves from the planned maintenance phase into the proactive environment, then the opportunity exists to provide additional non-financial rewards associated with involvement in problem solving, the acquisition of additional skills associated with a focus on precision maintenance and the minimisation of rework – but even here, managers need to be sensitive to the possible concerns of tradespeople that their involvement in these types of activities will ultimately lead to downsizing of the workforce and them, or their workmates, being made redundant. Once again, those organisations that have been successful in moving into this phase frequently use contractors to perform less critical, and less skilled, maintenance tasks, and use this pool of contract labour as the source for any job reductions – thereby minimising any negative feelings that tradespeople may have towards involvement in these activities.

Conclusion

What about the situation in your organisation? Put yourself in the heads of your people – engineers, maintenance supervisors, tradespeople, production supervisors, planners? What are the financial and non-financial rewards that these individuals receive from the work that they do? Are these consistent with the new behaviours and culture that you are trying to encourage? What can you do to remove financial and non-financial rewards that are inconsistent with desired behaviours? What can you do to introduce financial and non-financial rewards that encourage new, desired behaviours? Unless you successfully address the question of “what is in it for me”, then any process and systems changes will ultimately be unsuccessful.

If you are looking for further tips to shift your organisation from a reactive to proactive culture, the other articles in this series may be able to help:

Articles in this series