As pilot-in-command, James finished his routine scan of his instruments and then sat back. It was a beautiful day for flying; clear, cloudless skies and no turbulence. So far, it had been an uneventful flight, they had departed on time, with an almost-full aircraft – 237 passengers and a full complement of 10 cabin crew. They were expected to reach their destination slightly ahead of schedule. James looked out of the window to see the crinkled coastline slowly passing underneath them, 40,000 feet below. Even though he had thousands of hours of flying experience, and had flown this route dozens of times before, he never grew tired of that spectacular view.

Suddenly, his attention was drawn back to the aircraft. A shudder ran through the fuselage and up into his seat. The aircraft had suddenly pitched its nose down and had entered a steep descent. He looked across at his co-pilot, to find his co-pilot staring back at him – a look of slightly frightened surprise on his face.

“What’s happening?” asked James brusquely.

“I don’t know. I haven’t touched anything.” his co-pilot replied anxiously.

Their training kicked in. Hours spent in the simulator dealing with similar situations had helped them to immediately initiate the appropriate response procedure. Had the autopilot become disengaged? No it was still engaged.

Disengage the autopilot. Check.

Check airspeed. Too fast.

Throttle back engines and pull back on the stick to slowly recover level flight. Check.

Except that the engines wouldn’t respond to the command from the throttle. And the control joystick had no effect either.

“My control stick isn’t working,” said James to the co-pilot. “You have control.”

It soon became apparent that the co-pilot’s control stick was no more effective than James.

Reengage the autopilot and try to fly the aircraft using that. No. That doesn’t work either.

The cabin intercom buzzed urgently it was the senior cabin crew attendant wanting to know what was going on. Passengers were worried. Tell them that we have an incident up here that we are trying to resolve – and best to secure the cabin and prepare for an emergency landing”, James instructed.

Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. The co-pilot was making an emergency call on the radio. James hoped that they would be able to get out of this mess and it would be a false alarm, but there was an awful wrench in his stomach that told him that it may be a false hope. They had lost 15,000 feet of altitude already, and the aircraft was slowly but steadily continuing to gain speed – if they couldn’t regain control of the aircraft it was going to be touch and go whether they crashed into the ocean below, or broke up in the air.

OK. What is the fall-back procedure for the fly-by-wire system? James barked. Stress levels were high, and although he was trying to keep his emotions under control, it was difficult. The co-pilot initiated the self-diagnosis/recovery procedure for the aircraft control system. It seems to take an age – and then the recovery procedure fails.

“F##k!” yells James. “F##k! F##k F##k! What else can we try?”

And that is the last voice that is heard on the cockpit voice recorder before the aircraft plunges into the ocean taking 249 souls with it.

The above incident is entirely fictional. But if it were true, it would have made front-page news all around the world. People’s curiosity would have been piqued. In workplaces around the planet, lunch-room discussions would revolve around theories about what had happened, and what had caused this great tragedy. Some would wonder who to blame. And a few would wonder how best to stop accidents like from happening again.

Articles in this series

We are fascinated by disasters. We drive slowly by traffic accidents, rubber-necking to see if we can figure out what happened. We will dissect the latest tragedy in endless detail – and a lack of objective facts won’t stop us having an opinion. And the bigger the disaster, the better. Flight MH 370 (or MH 17), Deepwater Horizon, and for those enough old enough to remember them, Piper Alpha, the Challenger Space Shuttle and Exxon Valdez all generated discussions, theories and opinions by the bucket-load.

Yet every day in our workplaces mini-disasters similar to these, with similar common causes, occur with monotonous regularity. Billions of dollars of profit are flushed down the toilet, people are injured, permanently incapacitated and killed, and our planet is unnecessarily polluted because we allow these events to occur. And worse, we are either oblivious to those events, we don’t believe that they can be prevented, or don’t believe that it is worth preventing them. Sure, we investigate major incidents – especially those involving people’s health and safety, or significant environmental damage. But few permanent, long-term solutions ever result from those investigations. And for every major incident that we investigate, there are dozens or hundreds more that pass us by without so much as a cursory glance. We simply accept that failure is the price of doing business – we believe that failure, within reason, is acceptable.

Imagine if we took the same attitude to safety. That every fatality, that every injury was just the price of doing business. Thankfully, in most parts of the world, we don’t. And safety performance has improved immensely since we started taking safety seriously. It is time that we did the same with reliability.

If you don’t believe that the gains from improving reliability are significant, just imagine what it would be like at your workplace if:

- Equipment never failed unexpectedly

- Decisions that you made always had the desired effect

- Management processes always produced the desired outcomes

- People never made mistakes

An unrealistic nirvana? Probably but how far away from that nirvana are you at the moment? And how much closer could you get?

At this point, the maintenance folks amongst you are probably wondering, if everything worked when it was required to, and there were no unpleasant surprises, what the hell would I do with my time? I would probably be out of a job! But imagine what you could do with all the time that reliable equipment freed up. You could be focusing your efforts on actually improving things, rather than recovering from the latest crisis. You could be blessed with the gift of time to think, rather than being forced to act in haste. You could actually get home on time after work, rather than having to work overtime on resolving a breakdown. You may never get that dreaded phone call in the middle of the night.

That all sounds great, so far, but how do you actually improve reliability at your workplace? Especially when you are already flat out dealing with breakdowns. That is what we are going to explore in future articles in this series.

By way of introduction to what we are going to cover, let’s go back to our fictitious air crash at the start of this article. What caused this crash? We really don’t know, but there are a number of possible causes:

- The aircraft’s control system could have been inadequately designed, resulting in the pilots’ being unable to ever recover from whatever component failure caused this event.

- The pilots’ actions to recover from failure of the control system may have been inappropriate or inadequate

- The backup control systems may have been inadequately maintained or tested

- The components installed may have not met the required specifications for reliability

Each of these is, at this stage, a plausible cause of the crash. And each of these illustrate the various ways in which reliability is built into a functional system.

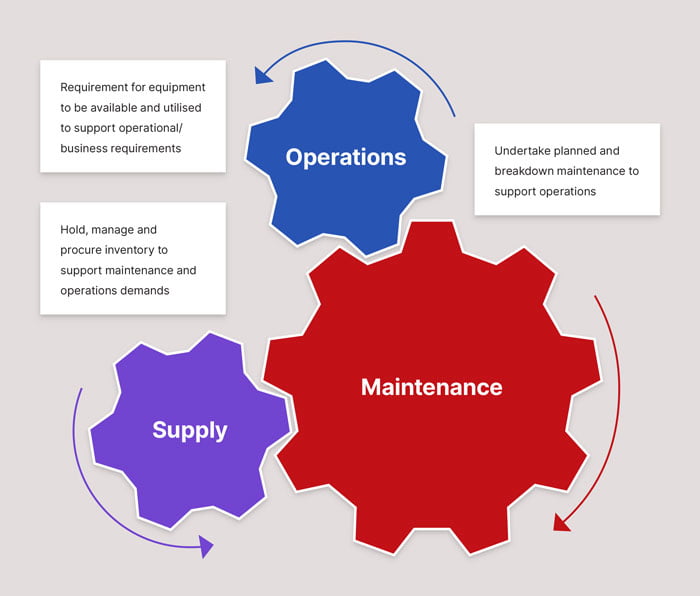

- Design – a system can only be as reliable as the reliability inherently built into its design. If the design is not inherently reliable, or resilient to failure, then reliability performance will always be limited.

- Operations – even the most reliable designs will not function reliably if operators do not operate the equipment as the designers intended it to be operated. Operating equipment outside its design limitations is a recipe for unreliable equipment.

- Maintenance – a system needs to be appropriately maintained in order for to remain reliable. In some cases, this includes the need to test and maintain backup systems

- Supply – a key element of the procurement function is to ensure that the items purchased meet the reliability performance standards specified or intended by the designers of the equipment. And a key requirement for stores people is to ensure that spare parts are cared for in such a manner that their reliability performance does not deteriorate over time.

It is tempting, for the uninitiated, to blame maintenance for all equipment failures. After all, they are the ones that are supposed to have preventive maintenance programs in place to prevent those failures. But as we can see from the discussion above, they often bear the consequences of other people’s decisions and actions. Yes, maintenance are generally the ones that are called on to repair the equipment after it has failed, but reliability is everyone’s responsibility. Improving reliability requires a cross-functional approach. And that cross-functional approach must also embrace Senior Management, whose decisions regarding funding and time-frames set the context within which equipment designers, operators, maintainers and supply personnel make their decisions.

If you would like to receive early notification of publication of these articles, sign up for our newsletter now. In the meantime, if you would like assistance in persuading your senior management of the need for a cross-functional approach to reliability improvement, and the value of doing so, please contact me. I would be delighted to assist you.