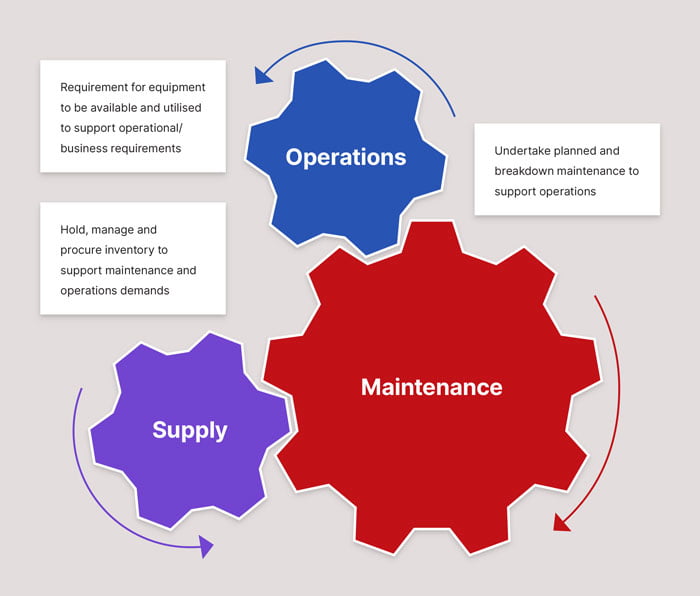

The function of Supply in procuring and warehousing of spares, are vital cogs in the machine that keep assets operating reliably. Yet often their role assuring this reliability is often not properly considered. Being at the tail end of the operational chain, Supply can often bear the brunt of poor decisions that were made by asset designers, or during asset operations and maintenance – the net result of which may be a tradesperson turning up at the warehouse counter with a broken part saying, “I don’t know what it is, but I need one of these, now!”

However, there are several things that Supply personnel can do to assure asset reliability and performance and in doing so, avoid being the source of the problem themselves; problems which in some cases could have substantial financial impacts to the business. In this article, we will explore how in four ways how Supply can assist with assuring asset reliability.

This is the fifth article in a series of eight articles on Reliability Improvement. The other articles in this series include:

Articles in this series

What can supply do to assure reliability?

When asking this question, let’s put the Supply function in some context. Generally, Supply staff are non-technical personnel who typically, but not always, reside in a functional arm of the organisation that is separate from Maintenance. Supply also operates in a business environment that typically places pressure, and measure performance, on minimising stock holdings and where possible, reducing the cost of procurement. Most organisations also typically have limited warehouse space, and not necessarily with the right conditions, to store the inventory that is being held. Consequently, in this context there are four main areas where Supply, as part of an integrated and co-ordinated effort to achieve value from the organisations’ asset, can support the assurance of asset reliability and performance through the following:

- Procuring the right spares

- Holding the right quantity of spares to support maintenance and operations

- Ensuring you are holding stock

- Making sure the spares are looked after while in storage, and

- Managing rotable/repairable spares

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Procuring the right spares

Within Supply, procurement officers can impact on equipment reliability if price (cost), rather than function and quality, is the overriding factor that drives a procurement decision. When purchasing spares, assurance of Form, Fit, Function and Quality (FFFQ) are key to asset performance and reliability. Buying the cheapest spare might have the same form, fit and function but not necessarily the quality to guarantee required level of asset performance and reliability that is needed to support the business. As an old television commercial once said, “Oils ain’t oils”.

Large parent asset Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs), eg. for vehicles, typically source ‘OEM spares’ from sub-supplier component OEMs. Consequently, while spares sourced from the parent asset OEM will have the required form, fit, function and quality to assure the performance and reliability requirements of the asset, these spares are typically much more expensive than if the same spare was procured directly from the sub-supplier component OEMs, ie. an overhead is added by the parent asset OEM. Your business rightly then tries to seek cost savings in spares procurement by finding suitable alternatives with the same FFFQ; but how can non-technical procurement staff make the right decision and not be swayed towards cost as the deciding factor? The key is to ensure that spares have a technical specification that captures their specific FFFQ, however, care must be taken not to make the specifications too restrictive such that is doesn’t permit effective market competition or innovation amongst potential alternate suppliers.

To solve this, procurement personnel must work collaboratively with Engineering/Maintenance staff to find and agree on the right spares supply. In the case of new or unknown suppliers, this could involve procuring samples and conducting formal operational trials where the performance and reliability of a spare can be assessed and inform subsequent procurement decisions.

For example, one organisation that we worked with established an on-line auction for gland packing for all of the pumps at their refinery. The lowest overall price that was obtained was from a new supplier (it was cheaper by a few cents per metre), and the procurement department were just about to switch suppliers when the Reliability Engineering group heard about the impending change. At that point, the organisation had never previously used this particular supplier’s packing at the refinery. At the Reliability Engineering groups insistence, it was agreed that the new packing would be trialled and the results assessed before changing suppliers. Subsequently the results of that trial indicated that the expected life of the packing offered by the alternate supplier used in the refinery’s operating environment would be about half of what had been established with the current supplier. Fortunately, in this case, the decision was made to stay with the incumbent supplier and a potentially very expensive decision was avoided.

In another example we encountered, the procurement officer, without consulting maintenance, decided to purchase 304 grade stainless steel bolts for an agitator in a process tank carrying highly acidic solution in lieu of specified higher quality 316 ‘marine’ grade stainless steel bolts. The 304 grade bolts were significantly cheaper and easier to procure (reduced supply lead time) than the higher quality 316 grade bolts that needed to be procured from overseas. In this case, cost and expediency were the deciding factors; especially when the non-technical procurement officer was told by the supplier, incorrectly, that there was no difference in the bolts. Consequently, in terms of Form, Fit and Function, the bolts were the same and without careful examination of the bolt markings, 304 grade bolts would easily pass off as the right bolts (especially as not all personnel were necessarily familiar with understanding bolt markings). However, the difference in Quality was to have a disastrous consequence for the business. Within a short period of time, the 304 bolts were eaten away causing agitator blades to detach. This resulted in significant production downtime and revenue loss to the business as the tank had to drained, cleaned, the agitator inspected and repaired with the correct 316 bolts on expedited procurement, and the tank refilled.

Both these examples show clearly that when Supply makes the decisions based primarily on cost, and not FFFQ, potential and actual catastrophic consequences can occur that generally result in significantly more expensive being borne by the business than any potential savings in cost from buying the cheaper item. Supply and Engineering/Maintenance need to work together to support the bigger business picture, rather than focusing on desired local drivers.

Holding the right quantity of spares

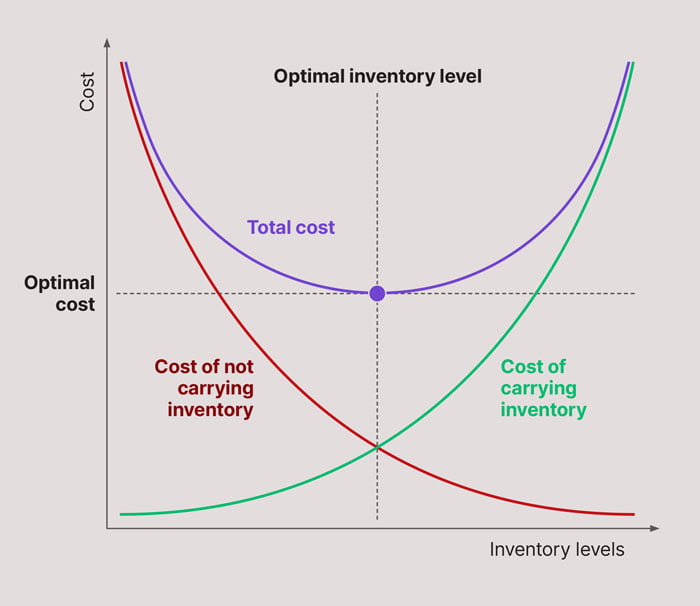

Now that we have the right spares, with the right FFFQ, Supply needs to ensure that these spares are held in the right quantities to meet required operational needs. Lack of spare parts when required can result in excessive downtime and/or potentially hazardous operations that expose the business to risk and financial loss. Not holding the spare, or it not being on the shelf at the time when needed, may also require high cost priority shipping in order to get the item to site as quickly as possible and minimise the downtime loss to the business. On the other hand, while holding excessive quantities of spares will minimise the downtime risk to the business, the business will incur significant holding costs associated with the procurement and storage of the items. This does not represent the best use of funds especially with limited budgets. Risks and costs need to be balanced such that an optimal level of stock is held to support operations, at an accepted level of risk associated with a stock out, at an acceptable level of cost in holding the spare.

Determining stock holding levels for each spare needs to consider:

- The scheduled Preventive Maintenance program which drives the demand for spares need for required maintenance tasks;

- Determining what critical spares can be expected to be used during the normal life of the asset that if not available when needed (ie. for corrective maintenance) would result in significant losses to the business;

- Determining what insurance spares that would not be expected to be used in the normal life of the asset that if not available when needed (ie. for breakdown corrective maintenance) would result in significant loss to the business;

- The lead time to procure and deliver the spare to your location;

- The risk of not holding the spare or not in the right quantity, ie. cost to the business of not carrying the item when downtime occurs; and

- The cost of holding the spare in the specified quantity.

Again, in making these decisions, Supply and Engineering/Maintenance need to work together to support the bigger business picture, rather than focusing on desired local drivers such as Supply wanting to minimise stock (to minimise costs) and Maintenance wanting to hold lots of everything (to minimise operational downtime).

Ensuring you are holding stock

With stock holdings of spares now optimised, the next step for Supply is to ensure that what the inventory management system says is being held in store, is actually what is in the store when it is required. It can be quite embarrassing and significantly costly to the business in downtime when the system says there is an item in stock when there isn’t. Not only that, but in situations where there is pressure to get equipment back to work, tradespeople will be tempted to simply refit the existing, damaged part, or substitute a lower quality part in order to meet operational requirements. This clearly will have an adverse impact on equipment reliability. To ensure physical holdings are correct, Supply needs to have processes in place that are diligently followed that include making sure that:

- Stock items are physically counted periodically and the tally compared to the recorded holdings in the inventory management system. Any discrepancies or damaged items discovered need to be replenished and replaced respectively with the causes for the discrepancies/damage investigated (to avoid reoccurrence in the future);

- Controlled access to the store is in place to prevent unauthorised personnel from accessing the store and allow the monitoring and movement of stock; especially during after-hours access by non-warehouse staff. Of note, Maintenance has an important role to play here in ensuring they report to warehouse staff the removal of any items of stock from the store, especially after hours when an unexpected breakdown is in urgent need of repair;

- Orders are placed to replenish stocks when the determined reorder point has been reached; and

- Orders to replenish stocks are followed up when the notified delivery date has passed.

Looking after spares in storage

Spares need to be kept under appropriate storage conditions to ensures that their condition does not deteriorate to the extent that it jeopardises its reliability such that it may be unserviceable when extracted from the store or fail a short time after it has been installed. When looking at storage of spares, the following questions should be considered:

- Does the spare need to be stored in a climate controlled environment? eg. electronics;

- Does the spare need to be stored under some form of cover that prevents/restricts exposure to sunlight and weather? eg. items with rubber;

- Does the spare have any openings that need to be covered or sealed to prevent the ingress of dust, dirt, insects, water and prevent corrosion?;

- Does the spare have any exposed surfaces that need to be protected to prevent corrosion? eg. sealed with Denso tape;

- Is the spare a fast-moving item or is likely to be rarely used, eg. insurance spare? This will influence the location of where the item will be physically stored;

Will the spare require any preventive maintenance whilst in storage? For example, motors whose shaft should be periodically rotated to prevent brinelling of bearings. This need for preventive maintenance in storage will influence the location of where the item will be physically stored and its orientation to facilitate the maintenance. Maintenance has an important role to play here in ensuring they identify as part of the item preventive maintenance program, any maintenance required whilst in storage and then complying with the required program as part of the assigned weekly schedule of work.

Certain spares may also have an indicative shelf life, i.e. use by date, by which time the item’s physical/functional condition will have deteriorated to a point where it will not be able to deliver the required level of performance/reliability. Some examples of spares with a shelf life include:

- Hoses and belts (For example. RMA IP3 4:2007 Power Transmission Belt Technical Bulletin – Storage of Power Transmission Belts states 8 years under specified conditions)

- O rings

- Batteries

- Batteries on circuit cards

- Sealants, adhesives and chemicals

- Oils and lubricants

- Paints

Consequently, Supply needs to have processes and documentation in place to ensure spares with specific storage requirements are identified and that any spares with shelf life limitations are appropriately managed.

Managing repairable/rotable spares

In addition to the considerations mentioned above, repairable/rotable spares add another dimension for consideration. When a repairable/rotable spare has failed and is removed from the parent asset, it then needs to be repaired before the spare can be returned and accounted for as a serviceable asset for issue from the store. The management of repairable/rotable items is a topic in itself and will be the subject of a future article. It is an activity that requires both Supply and Maintenance working together to ensure serviceable repairable/rotable spares are in stock when needed to avoid unnecessary asset downtime and loss to the business. By having a managed process for repairable/rotable spares in place, you’ll avoid situations like needing the spare gearbox to restore the plant to operation only to find it sitting in the warehouse yard where it had sat unrepaired for a number of years after it was previously removed from service.