Can’t we all just get along?

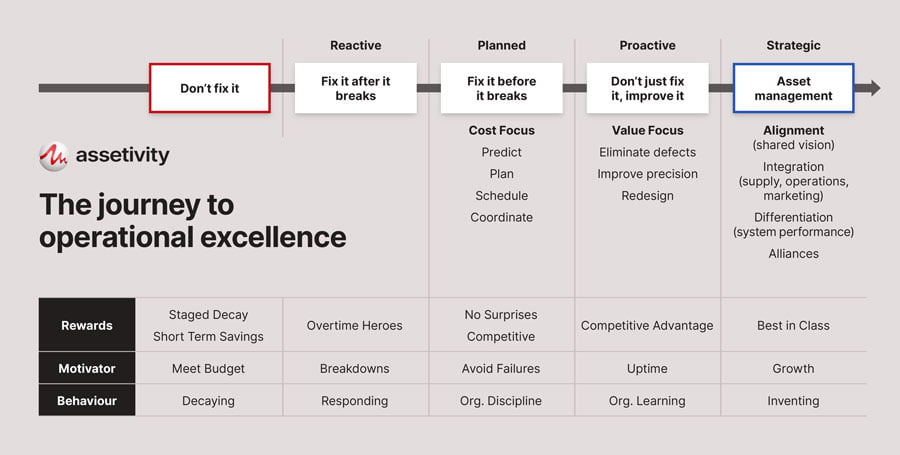

Another clear differentiator between organisations that are achieving a more reliability-focused culture and those that are not, is the level of teamwork and cooperation between different functions and departments. Once again, refer to Figure 2. This diagram is based on insights gained by Winson Ledet during his time at Dupont Chemicals and Specialties, and subsequently published by him. It is particularly valuable in terms of illustrating and understanding the cultural implications associated with moving from a Repair-based to a Reliability-based organisation.

This is the fourth in a series of 6 articles on moving from a repair-focused to a reliability-focused culture.

Articles in this series

In a Reactive Maintenance environment, the interaction between Production and Maintenance is pretty simple. Production says “jump”, and Maintenance says “how high?” Once again, some people would refer to this as being “customer oriented” – I would call this being a slave to Production’s whims.

As organisations move into the Planned Maintenance environment, however, the nature of the relationship between Production and Maintenance changes. If Maintenance is to effectively schedule routine maintenance tasks (PMs, inspections etc.) as well as planned repairs, then it must reach agreement with Production regarding the most appropriate time to perform this activity, and Production must ensure that the equipment is shutdown, isolated, and in some instances, cleaned, ready for maintenance.

In this case, it is Maintenance now initiating the request that Production perform some activity – communication and customer orientation is no longer all one way.

Defining and allocating responsibility

As we move even further up the path to reliability, and we start to embrace such principles as Reliability Centred Maintenance (RCM) and PM Optimisation (PMO), there is a recognition that there is a need for a better definition of maintenance. In accordance with the principles of RCM, maintenance can be defined as:

“any activity carried out on an asset in order to ensure that the asset continues to perform its intended functions, or to repair the equipment”

If we adopt this definition, then which of the following activities are actually “maintenance”?

- Routine cleaning

- Visual inspections

- Minor adjustments

- Setpoint adjustments

- Condition Monitoring

- Equipment Performance Monitoring

- Overhauls

- Repairs

And who actually performs these activities? In most organisations, it is both operations/production and maintenance personnel. In fact, it can be argued that, in most continuous process operations, most of the work that Production personnel do is actually “maintenance”. The late John Moubray (accurately, in my view) once described most production operators as being “machine minders” – in other words, most of their work is associated with making sure that machines “continue to perform their intended functions”.

So in using RCM and PMO processes to determine the optimal “maintenance” program for plant and equipment, there is an explicit need to involve both maintenance and production personnel, and arrive at an appropriate division of responsibilities between the two groups.

Adopting a failure elimination approach

The concept of “operator/maintainer” is also one of the concepts within Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) processes.

As we move into Proactive Maintenance techniques, such as Failure analysis and elimination processes, effective use of these techniques leads us to understand that “sometimes things break, and sometimes they get broken”. That is, that the way equipment is operated, and the environment within which it is operated, is often the reason for equipment failure, rather than any equipment-specific issues. In the civil aviation industry, for example, equipment failure is currently responsible for less than 15% of air crashes – the remainder is due to “pilot error” and environmental conditions. A focus on failure elimination forces us to think more carefully about:

- Ensuring that we are using the right equipment/components for the job (requiring better teamwork between Maintenance and Engineering), and

- Ensuring that equipment is operated within its design envelope (requiring yet more teamwork and cooperation between Maintenance and Production)

Thinking strategically

And finally, as we move to the Strategic domain, we focus on whole-of-life Asset Management. Asset Management is defined in ISO 55000 as being:

“coordinated activity of an organisation to realise value from assets”

Effective Asset Management requires even wider cross functional collaboration and alignment – one which embraces business functions including Finance, Sales and Marketing, Human Resources and potentially others. Building this cross functional collaboration and teamwork is an absolutely vital part of moving to a Reliability-Focused culture.

If you are looking for further tips to shift your organisation from a reactive to proactive culture, the other articles in this series may be able to help:

Articles in this series