Often, we see organisations embark on large-scale Preventive Maintenance program improvement projects (and sometimes even finish them!) using Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) or PM Optimisation (PMO) processes, and then ignore their ongoing refinement for several years (or more).

They then embark on another large-scale RCM or PMO project to rectify the many unresolved problems that have been allowed to develop in their Preventive Maintenance routines. While this is great news for PM Development contractors, it is not great for their clients. It is far better to embed continuous improvement of the Preventive Maintenance program as part of normal, day to day business. This article will outline some ideas on how to make that happen. But first we will discuss the benefits of a continuous improvement approach.

The benefits of making preventive maintenance a living program

The benefits of continuous improvement of your PM program are two-fold. First, large-scale RCM and PMO projects are resource-intensive and difficult to manage. Frequently external resources are required to complete the work within a reasonable timeframe, and where internal resources are required to provide the necessary local knowledge and experience to assist with the project, the demands on their time can also be significacnt. On the other hand, the workloads associated with ongoing, incremental refinement and improvement are much easier to manage. Second, and more important, every day that passes where a PM improvement opportunity is not implemented represents a lost opportunity (in terms of cost reduction, risk reduction, or profit improvement) relating to Maintenance Performance for the organisation. Without ongoing maintenance and improvement, the laws of physics apply – entropy means that your Preventive Maintenance system decays over time. Without an injection of energy and improvement, the performance of that system also decays.

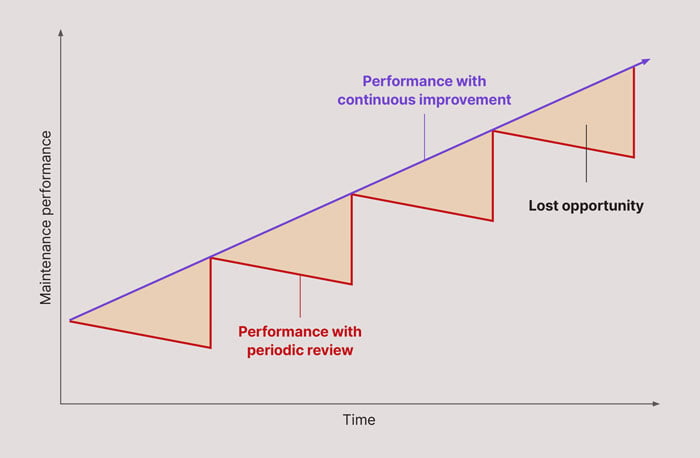

We can illustrate that conceptually in the following chart:

In this case, the area between the green and the blue lines represents a loss of Maintenance Performance that is avoidable, if a continuous improvement approach was in place.

Continuous improvement triggers

So, what are the triggers that should initiate a review of your Preventive Maintenance Program. We consider that there are four main triggers:

- Unexpected Equipment Failure

- Modifications to the Equipment

- Changes in Operating Conditions or Context

- Changes in the External Environment

Unexpected equipment failures

In theory, any unexpected equipment failure should be subjected to some form of analysis – ideally using Root Cause Analysis (RCA) techniques. In practice, this is hard to implement in most organisations, as there are frequently more failures than there is time to effectively analyse. As a result, it is often only the most significant failures that are subjected to formal RCA processes. Where this is the case, you should make sure that the team performing the analysis considers the adequacy of the current Preventive Maintenance program as part of its assessment. They should also be sure to apply appropriate reliability principles (such as Reliability Centered Maintenance) when performing this assessment.

But even when there is not sufficient time to perform a full Root Cause Analysis investigation, there is no reason why a Reliability Engineer (or experienced, and properly trained Maintenance Planner) could not perform a quick, on-the-spot review (again using RCM principles) to assess whether a revised PM program would assist in preventing the failure from recurring.

One of the traps to avoid, however, is to automatically assume that Preventive Maintenance can prevent all failures, and to then apply an inappropriate Preventive Maintenance task. For example, a failure that occurs as a result of operator error is highly unlikely to be successfully addressed through additional Preventive Maintenance. Without suitable, objective, analysis, you can quickly find that more and more Preventive Maintenance tasks get added, and many of these will at best be a complete waste of time, and at worst, may actually induce additional equipment failures themselves.

The key message is that if you are going to review your PM program after unexpected failures, then you must follow a defined process, and those applying the process must clearly understand Reliability Centered Maintenance principles. Some training in RCM and PMO is essential, if the skills are not yet fully embedded.

Modifications to the equipment

It is clear that any time a piece of equipment is modified, the Preventive Maintenance routines associated with it must also be reviewed. This should be an essential part of any technical Management of Change process. If additional components are added, then these may require additional Preventive Maintenance. If items are removed, then the associated PM tasks must also be removed. If a component is changed or modified, then the Preventive Maintenance program may also need to be modified.

Most people would recognise this simple fact, yet unfortunately, in many organisations, the PM review activity does not occur. And in even more cases, if it does occur, it generally happens sometime after the modified equipment has been installed and commissioned. For effective reliability performance, disciplines must be put in place to ensure that this happens BEFORE the equipment enters service.

While the direct impact on equipment reliability of failing to review the PM program for modified equipment is evident, the indirect impact can often be even greater. Frequently, even small errors in the PM routines given to tradesmen or craftsmen to perform can lead to them losing faith in the quality and accuracy of the entire PM program. And the longer that these errors exist, then the less trust these people place in the PM routines. This can then lead to them ignoring large parts of the PM routines, especially when they believe that they know better than those who have prepared the routine. “Good” inspections can then be replaced by “Poor” or even “No” inspections, and potentially lead to a significant deterioration in overall plant reliability.

Changes in operating conditions or context

Changes in operating conditions or context should also be a trigger for review and improvement of the Preventive Maintenance program. These changes could include:

- Increased or reduced performance demands on the equipment (e.g. production output)

- Changes in the specifications of input materials or expected output quality

For example, at a mine site, changes in ore grade or the material properties of the ore being processed may lead to requirements for different preventive maintenance.

Similarly, a significant increase in the production output required from a machine may require different preventive maintenance in order to ensure that the equipment can continue to meet its performance expectations.

Often the ideal time to perform this review is as part of the corporate Annual Planning/Budgeting process. It is generally at this time that the operating demands and operating context for the equipment are determined for the next 12 months. Any significant changes should then trigger a formal review of the Preventive Maintenance Program for affected equipment.

Changes in the external environment

The final trigger for a PM program review should be whenever the external environment changes in particular, when the regulatory environment changes. Changes in regulations or standards relating to the equipment may require modifications to the Preventive Maintenance program relating to statutory inspections or replacements.

However, other changes may also trigger a need to review the PM program. For example, increased public pressure relating to environmental protection may lead you to initiate a review of those Preventive Maintenance activities that mitigate environmental risks, regardless of the regulatory environment.

Periodic review

Even if you do respond to the triggers listed above, this will not eliminate the need for periodic review of the PM program. All PM programs are developed with incomplete and potentially inaccurate data, and assumptions are invariably made when determining the most appropriate Preventive Maintenance tasks. However, as time passes, and more experience is gained and knowledge captured regarding the equipment (and how, and how often, it fails), then some of those assumptions can be reviewed and refined.

If equipment is NOT failing, it does not necessarily mean that the Preventive Maintenance program is optimal. There may be opportunity to reduce the frequency of some tasks or even to eliminate the tasks altogether. This can only realistically be assessed during some form of periodic review. We would recommend that this occur annually or biennially, although more stable operations may be able to extend this interval.

Implementing continuous improvement of your preventive maintenance program

As has been indicated earlier in this article, the keys to successful implementation of a continuous improvement effort are:

- Establish and document formal continuous improvement processes which respond to the triggers above, as well as initiate periodic formal review of the PM program

- Ensure that all personnel are aware of, and have the skills to apply, the documented processes. A sound knowledge of Preventive Maintenance program development and review processes and principles is essential

However, all of this will be to no avail if the organisation does not have the discipline to follow the processes that have been established. Ensuring this discipline is in place is a significant topic in its own right, and beyond the scope of this article, but three of the key elements required are:

- Leadership – someone in a position of responsibility need to make sure that the work required is actually done

- Accountability – clear accountabilities and responsibilities for ensuring that the processes are followed must be established, and

- Reward Systems – the organisation’s reward systems (both formal and informal) need to ensure that those who make continuous improvements to the PM system are recognised for the valuable contribution that they make in this area.

Conclusion

I hope you have found this article useful. We would be delighted to help you to develop and implement the processes discussed above, and to ensure that your people have the skills and abilities to effectively implement them. Please contact us today for a free, obligation-free discussion.