In the first in this series of articles, we discussed the benefits that leading organisations enjoy when they have high levels of maintenance productivity, and outlined methods for achieving this. Since then, we’ve been working through the proposed methods and examining how each can be used to eliminate waste to deliver lean maintenance with improved productivity. In this article, we will tackle the final topic on this list, thinking holistically.

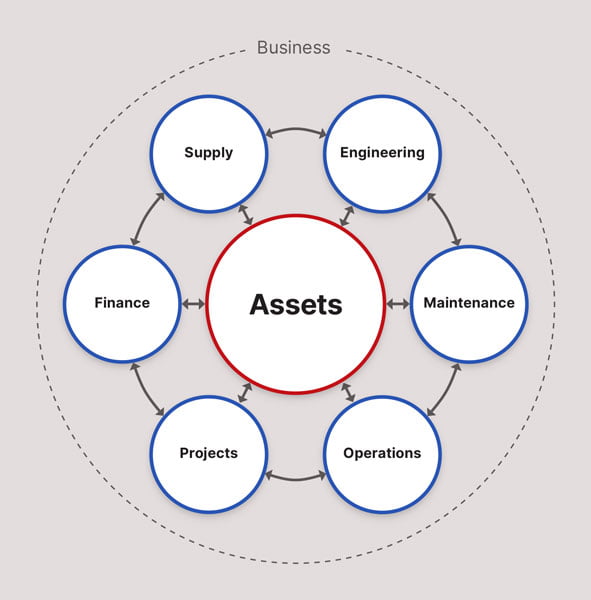

If you’ve been following along, you will have a reasonable sense of what the maintenance department can do internally to eliminate waste. Now it is time to think more broadly about factors that influence maintenance productivity. These factors inevitably include the interfaces with a wide range of other departments or functions that interact with Maintenance to deliver value through assets, as illustrated in the following figure:

In addition, there will also be interfaces with service functions at the back end of the organisation, such as Human Resources and Safety and Environment, that will influence maintenance productivity. This is because there are requirements on both parties at each interface to deliver services or products to particular standards in order to achieve the organisation’s goals. These requirements create further requirements to adequately define the standards and each requirement creates potential for waste if it is not met. Here are some common examples of such waste:

- Operations:

- Cause extra (inefficient) breakdown maintenance by operating outside of equipment limits (accidentally or deliberately)

- Transfer clean up or common equipment care tasks to maintenance rather than using operators

- Supply:

- Cause re-work by supplying incorrect or deteriorated parts

- Delay maintenance (or incur temporary repairs) by not having parts available when required

- Drive repair tasks by buying cheaper, lower reliability parts

- Delay tasks by engaging contractors or hire equipment that is not capable of doing the task to the required standard

- Projects:

- Cause high maintenance workloads by underspecifying equipment for the expected loads, leading to frequent failures

- Extend maintenance duration by providing restricted (or no!) access to commonly maintained items

- Drive errors through supply of incomplete or incorrect maintenance documentation

- Transfer maintenance readiness tasks onto the maintenance department

- Human Resources:

- Drive maintenance quality and time issues by recruiting personnel with limited or inappropriate skills, experience or attitude

- Learning and Development:

- Reduce productivity by cancelling or rescheduling essential maintenance or technical training

- Reduce productivity by increasing non-maintenance “essential” training

- Safety and Environment:

- Reduce productivity by increasing the paperwork requirements to commence maintenance

- The Executive:

- Demand ineffective additions to the maintenance program in response to rare failures (see “Doing the right work”)

- Drive all of the above by setting budgets, plans and policies for the organisation

In addition, there are external organisations that can lead to waste in maintenance:

- Regulators:

- Reduce maintenance productivity by specifying non-value adding tasks or excessively high frequencies

- Contractors:

- Consume maintenance resources in supervisory and administrative capacities

- Cause rework by not performing work to the required standard

If you’ve never seen any of the above, then you are very lucky – we see problems like these in every organisation we work with. So assuming you have some of these issues, what should you do about them? In order to answer this, we need to talk a bit more about why these issues occur.

We see more of the above issues in organisations that are heavily “siloed” – i.e. where individuals operate within functional/departmental boundaries with very limited interactions between these functions. Operations don’t talk to Projects, Projects don’t talk to Supply and NOBODY talks to Maintenance (in the worst case, the Electricians don’t even talk to the Fitters!). In these types of organisations, misunderstanding of requirements at the interfaces is inevitable. Since each function is dependent on the others, a destructive pattern tends to develop:

- Regardless of intent, functions lack the visibility to make good, holistic decisions that balance competing needs across the organisation

- In the absence of better information, individuals will go with what they know, and make decisions that are good for their functional area

- Decisions that clearly favour one function’s needs over another break down essential trust, creating an “us and them” culture that leads to a downwards spiral

It is clear, then, that solutions should focus on breaking down the silos and promoting communication/engagement between the functions. That is, everybody should be thinking holistically. Since every interface carries requirements on both parties, either party can start the improvement process, so please don’t wait for them to engage you. Reach out – you might be surprised what happens.

There are a range of tools that might be of assistance in achieving this, depending on your organisational needs:

- Shared/Aligned KPIs – we all know that “what gets measured gets managed”, so issuing shared KPIs can be a great way of motivating different functions to work together. What would operations do differently if they had 50% of their bonus dependent on achieving a certain reliability or maintenance schedule compliance goal? For more on KPIs, see our article Using Performance Measures to Drive Maintenance and Asset Management Performance Improvement.

- Shared Meetings – sure, we’ve all wasted a lot of time in meetings, but they are still an important business tool if used correctly. One of the key mechanisms for doing this is to invite the right people. If you hold a weekly planning meeting but don’t invite Supply or Operations, don’t be surprised when parts or equipment are not available when needed. Equally, if you want particular maintenance requirements designed into new equipment, make sure that you send an appropriate representative to Projects meetings. Don’t be afraid to ask (politely) if they don’t offer – this is for the good of the overall organisation after all.

- Shared Facilities – if the first time you meet somebody is when you need something from them, chances are you won’t get it. Promote informal engagement between staff – at all levels – by sharing facilities, particularly crib rooms. You can reinforce this by holding shared functions and activities to promote a “one team” message.

- Defined Responsibilities – everybody benefits when responsibilities are clearly defined and we find that the RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) tool is an excellent way of accomplishing this. Once roles are defined, efficient execution can be planned. For example, if Maintenance has been allocated clean up responsibilities, then the maintenance workforce can be structured to include a limited number of “general hands” with appropriate (low) skills. Without this clear allocation, a much more expensive technician or process operator might end up doing the work.

The bottom line here is that most people are not idiots and the easiest way to discover this is to spend time with them. You may still disagree with what they want to do or how they want to do it, but you will probably understand why. From there, you can communicate what maintenance needs and why it is important, given you an even chance bet of achieving it.

The above principles apply to a lesser extent with third parties. You may not exactly share KPIs with your regulators, contractors or customers, but you should certainly have regular meetings with them to understand their changing needs and to simply keep the communications channels open.

One more thing – don’t ever expect to get everything you want. It may be perfectly legitimate for operators to exceed limits to deliver a high priority order or to take advantage of market conditions, the supply department should not be holding rarely used, expensive and readily available spares and project might trade off maintenance costs for acquisition costs. As long as these decisions are made knowingly, with a full understanding of the repercussions, then the role of maintenance is to do the best with what they’ve got. Of course, it is always worth asking to make sure the repercussions are understood.

Do you need a more effective preventive maintenance program?

We have over 21 years of experience in improving maintenance programs for a wide range of industries. Our services are catered to your specific business and operational goals, and we aim to be proactive in delivering solutions that are grounded in practicality and bottom-line results. Sound good to you?