In our last article, we looked at what asset management was, and concluded that it was a fundamentally different way of thinking about physical assets and how they deliver value to an organisation. In this article, we will look at what this means in practice.

To start, recall our definition of asset management from the British Standards Institute’s Publically Available Specification No. 55:2008 (PAS 55): (you may recall three definitions of asset management – but this is the longest and we consultants get paid by the hour!)

Systematic and coordinated activities and practices through which an organisation optimally and sustainably manages its assets and asset systems, their associated performance, risks and expenditures over their lifecycles for the purpose of achieving its organisational strategic plan.

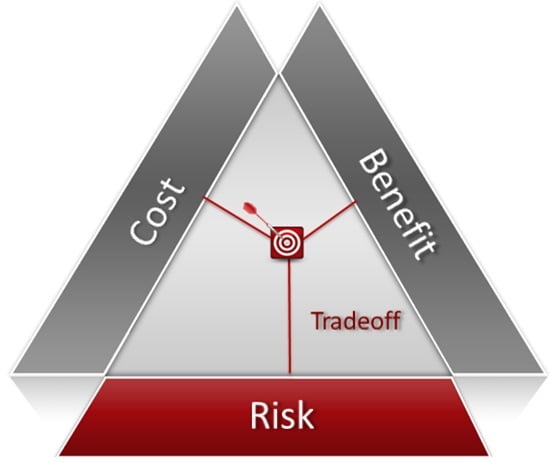

There are a few key words highlighted that we didn’t dwell on in the last article. The idea here is that managing assets delivers value either by increasing performance/benefits, reducing business risk (safety, but also corporate reputation and so on) or reducing cost. Further, there is a tension between these factors where, in a well-managed system, improving one factor will necessarily cause deterioration in at least one other. This trade-off is illustrated below, where the further you move from any side of the triangle, the further you move from “optimum” (zero cost, zero risk, perfect benefits) in that regard.

There is hidden complexity in this diagram. Firstly, this trade-off can be applied through each life cycle phase – for example, increasing maintenance spending will usually deliver better performance and lower risk. Similarly, reducing the budget for an acquisition project will usually deliver a lower performing, more risky asset. Equivalent examples can be drawn for operation and disposal.

Next, note the “usually” in the above examples – applying best practice techniques such as Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) and Systems Engineering can “shrink” the triangle, so that the trade-off is simultaneously closer to all of the optimum positions.

Lastly, there will be an overall “optimum” position for every asset in every life cycle phase in every organisation. In the above diagram, cost and risk have been traded to obtain improved benefits, however this is only one possibility. The “optimum” point depends on the business – if you are a cash-strapped start-up, you might be prepared to accept lower performance and higher risk to meet your capital cost constraint and actually start producing. If you are a government-owned utility, you might take a longer term view and seek to spend more on acquisition to reduce risk or increase performance. This trade-off will also be influenced by time – for example, the optimal position for a miner nearing the end of mine life may move towards lower performance and higher risk to avoid the cost of a major upgrade or refurbishment that will not be recovered in the available life.

All of this brings us to the point of this article. What is it that asset management does to add value to an organisation? There are several answers:

- Acknowledgement of business needs – all asset management approaches acknowledge the variability in “optimum” associated with the business context and endorse rational decisions made on the basis of such factors.

- Promotion of best practice – adoption of techniques such as RCM and Systems Engineering is implicit in standards such as PAS 55 and ISO 55000 and explicit in broader asset management documentation, such as the UK Institute of Asset Management’s “Asset Management – an Anatomy”. As discussed, these techniques tend to shrink the optimisation triangle so that all acceptable solutions are simultaneously closer to optimum in each dimension.

- Support to decision making – the concept of line of sight explicitly requires that decision makers at all levels are aware of both the corporate goals flowing down from above and the asset performance/cost/risk information flowing up from below. Decision makers are then able to answer the following questions:

- What performance is being delivered?

- What performance is desired?

- How much are we prepared to pay to close the gap?

- What is the tolerable level of risk?

Nothing is perfect and the true optimal trade-off between performance, cost and risk can never be known. The strength of the asset management approach, however, is to acknowledge this imperfection and build a continuous feedback loop to adjust the way assets are acquired, operated, maintained and disposed so that a reasonable approximation to optimal is achieved.

If you enjoyed this article and want to receive notifications of future articles that we publish, please sign up for our newsletter here.